TAMPA, Fla. (WFLA) — It may seem counterintuitive, but the world is simultaneously getting wetter and drier, due to climate change. Certain areas are getting wetter, and others drier, while some are seeing both happen at the same time. How is that possible?

Human-caused climate change is heating our planet, adding massive amounts of energy to the climate system. Simple math tells us a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture and dumps more rain. That is true in most parts of the planet.

But at the same time, climate change is drying the Earth’s surface. Even if more rain falls in some places, more heat equals more evaporation, thus more water is being stripped from land than is added due to extra rainfall. So these areas are drying out.

Lastly, storm patterns are becoming less consistent in some places. One year you may get successive extreme storm events along the U.S. West Coast, while the next year storms may be hard to come by. This is called weather whiplash, and the lead scientist studying this discipline, Dr. Daniel Swain, says weather whiplash is increasing much faster than the climate models project it will.

The jagged red and blue lines in the tweet below show the observed weather whiplash (wet and dry periods) versus what the models project in the dashed lines. While both observations and models say weather whiplash is and will increase, it is clear that the reality is faster than the model projections.

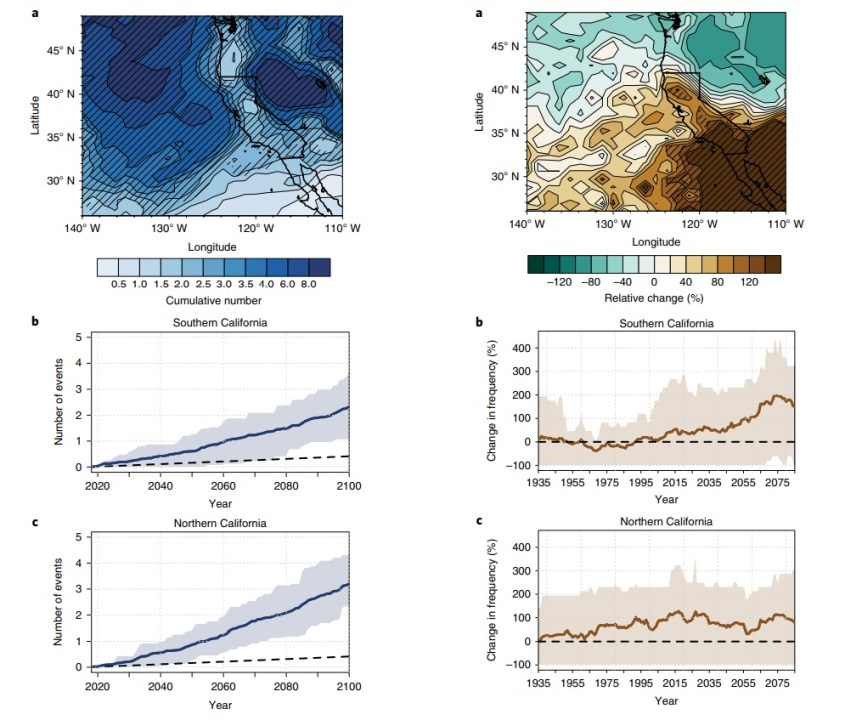

You can see this increase in whiplash by looking at the below image from Dr. Daniel Swain. On the left, the blue shading shows that extreme precipitation events are increasing or will increase in California in the coming decades. While on the right side, you can also see the brown shading increases, showing extremely dry years will also increase markedly.

This is obviously a problem for water management, in terms of both drought and flood. More extreme successive storm systems can overwhelm flood controls. The vast majority of flood damage in California comes from atmospheric rivers which bring extreme rain rates.

In the image below (Huang Et al. 2020) you can see how atmospheric rivers are expected to increase in intensity over the coming decades.

On the flip side, more drought means more intense – larger wildfires and less water for communities and farming. The impact of escalating homeowners insurance, from both drought and flood, is already debilitating.

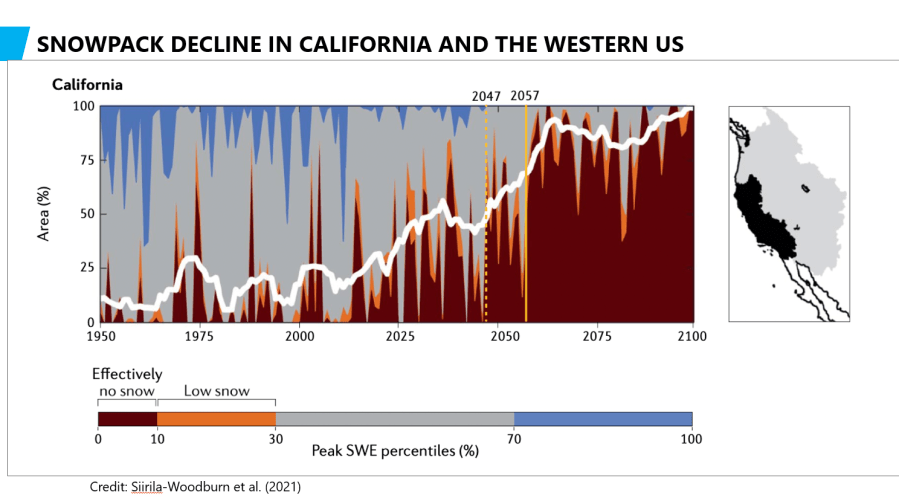

In California, 80% of runoff comes from snowpack, which drains into reservoirs. Thus the massive population of California heavily relies on snow melt for its water supply for human consumption and agriculture.

But due to a warmer climate (earlier and faster melting, and warmer-wetter snowfalls) and increases in weather whiplash, the Sierra-Nevada mountain range in California is experiencing a worrying decrease in snowpack, thus the water it makes available when it melts.

The image below shows the decline in the area of snowpack (and water runoff) in the Western U.S. and California. The red shading projects when there will be little to no snow cover. You can see that the snow cover area – and thus the water from runoff – almost disappears by the mid-late century. This would be a huge problem for the Western U.S.

In today’s Climate Classroom we are interviewing the head of the Central Sierra Snow Lab at UC Berkeley in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California, Dr. Andrew Schwartz. He monitors the year-to-year snowfall and runoff into California’s reservoirs. As part of his job, he has witnessed the fast changes occurring in the state.

WFLA’s Chief Meteorologist and Climate Specialist Jeff Berardelli met Dr. Schwartz at a climate and weather conference called Operation Sierra Storm in Lake Tahoe in January. The conference provided some eye opening information about how the climate is changing, focused on the Western US.