TAMPA, Fla. (WFLA) — In recent months, three new studies have found significant changes in hurricanes due to a warmer climate that apply directly to storms in the Gulf of Mexico. This likely means greater risk and bigger impacts to many Gulf Coast communities in the future.

The three studies focused on different impacts from a warming climate: earlier season intense hurricanes, heavier rainfall, and changes in steering flow.

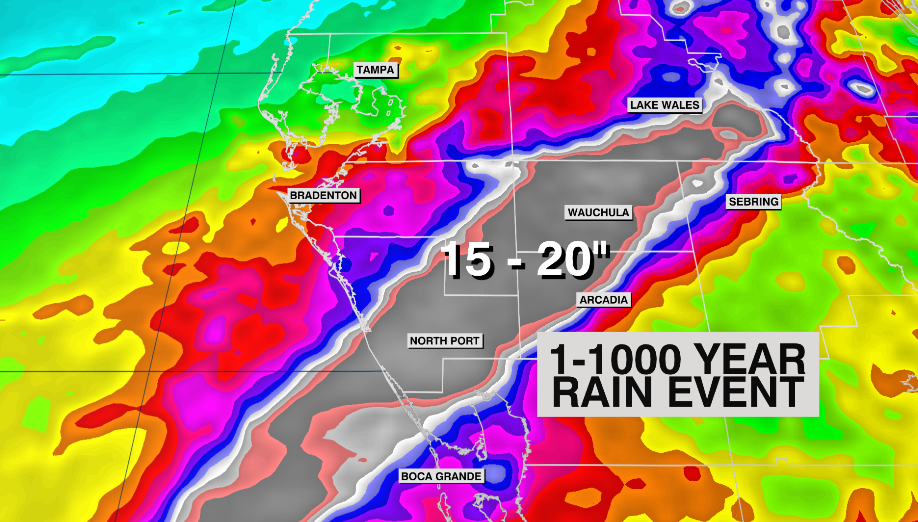

In a study submitted and reviewed, but not yet published in IOP Science, long-time hurricane and climate researcher Dr. Michael Wehner found that a warmer climate made 2022’s Hurricane Ian – which dropped a swath of over 20″ of rain from southern Sarasota to Southern Polk counties (a 1-in-1000 year event) – was made 18% wetter due to a warmer climate.

This research is known as a real-time attribution study. It allows climate scientists to ascertain how much of an impact man-made climate change had on a given extreme weather event.

There is a well-known and simple mathematical relationship called Clausius-Clapeyron (CC) that tells us for every 2-degree Fahrenheit increase in air temperature, the atmosphere can hold 8% more moisture. Global air temperatures have warmed by about 2 degrees F since 1900.

But in the case of intense storms like Ian, that relationship underplays the increase in rainfall. That’s because stronger hurricanes have more intense rainfall rates and can more easily aggregate environmental moisture. In some cases, like Ian and Harvey, the rainfall ends up more than two-to-three the CC relationship.

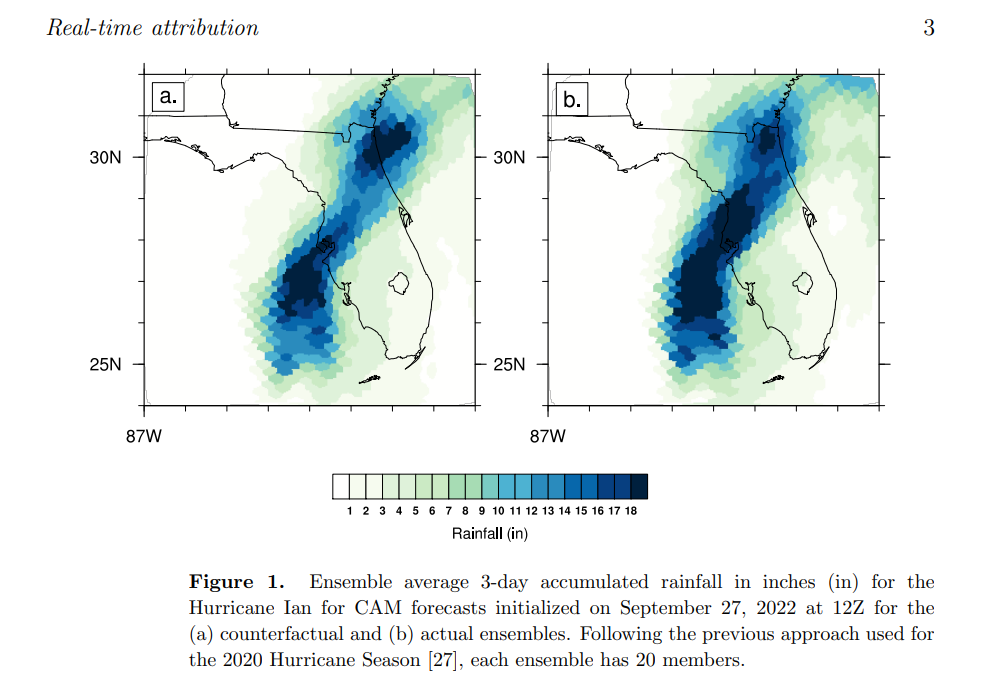

In the image below from the paper, Hurricane Ian rainfall is shown using climate models to simulate it. On the left shows rainfall in a world without human-caused climate change. On the right, the computer model ensemble shows rainfall in our now warmer world. You can clearly see the image on the right is wetter, due to climate change.

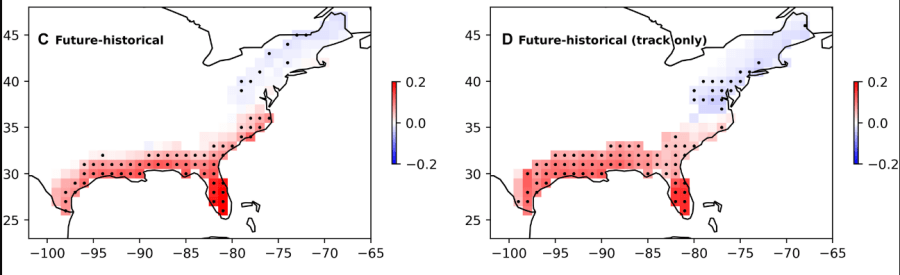

It’s not only rainfall that is changing due to a warming climate, it may also be steering flow and shear. In a paper published in April of this year, co-authored by Dr. Michael Wehner, the researchers find that the US coast is at increased risk from hurricanes due to climate change.

The team examined past, current, and future projections of hurricane activity (1980–2100) using climate and a synthetic hurricane model. The results show an enhanced hurricane frequency for the Gulf and lower East Coast regions.

In the image below from the paper, increases in hurricane risk are indicated by the red shading.

The increase in coastal hurricane frequency is driven primarily by changes in steering flow, which can be attributed to the development of an upper-level cyclonic (counterclockwise) circulation over the western Atlantic, forced mainly by increased heating in the eastern tropical Pacific. This was a robust signal across the multi-model ensemble they used for the study.

Turns out, these heating changes also play a key role in decreasing wind shear near the U.S. coast, which further enhances hurricane risk near the U.S. coast. Decreased wind shear allows systems to maintain organization, or even intensify, without being interrupted by environmental winds.

WFLA’s Chief Meteorologist and Climate Specialist spoke to Dr. Wehner in his weekly Climate Classroom show on Thursday. Dr. Wehner said the results are robust and are concerning for US coastal communities near the Gulf of Mexico and Southeast.

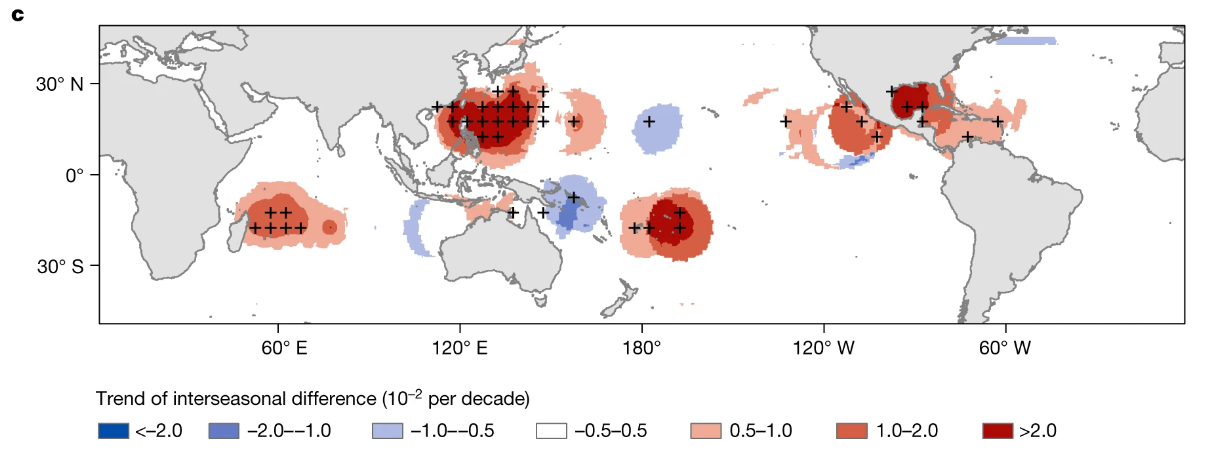

And lastly, in a paper published on Wednesday, the authors found that intense hurricanes – with winds of 127 mph or greater – are happening earlier in the season. In the Northern Hemisphere, that trend is 3.7 days per decade since 1981. That means, on average, hurricanes reach this intensity about 15 days earlier than they did just 40 years ago.

This earlier trend applies to rapid intensification as well. The greatest trend of earlier intense hurricanes was found in the western Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico, as noted by the red shading. The authors found the reason for this is warmer waters due to man-made greenhouse warming.