TAMPA, Fla. (WFLA) — Ahead of the Dec. 3 jobs report by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, previous reports on the record number of employees leaving their jobs, drops in worker wages and a study on job flexibility may shine a light on the American workforce’s behavior.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, quits were about 3.6 million according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

September’s quits rate was a historic high, according to the BLS. 4.4 million people left their jobs, willingly, contributing to an increase of 3% compared to previous monthly levels.

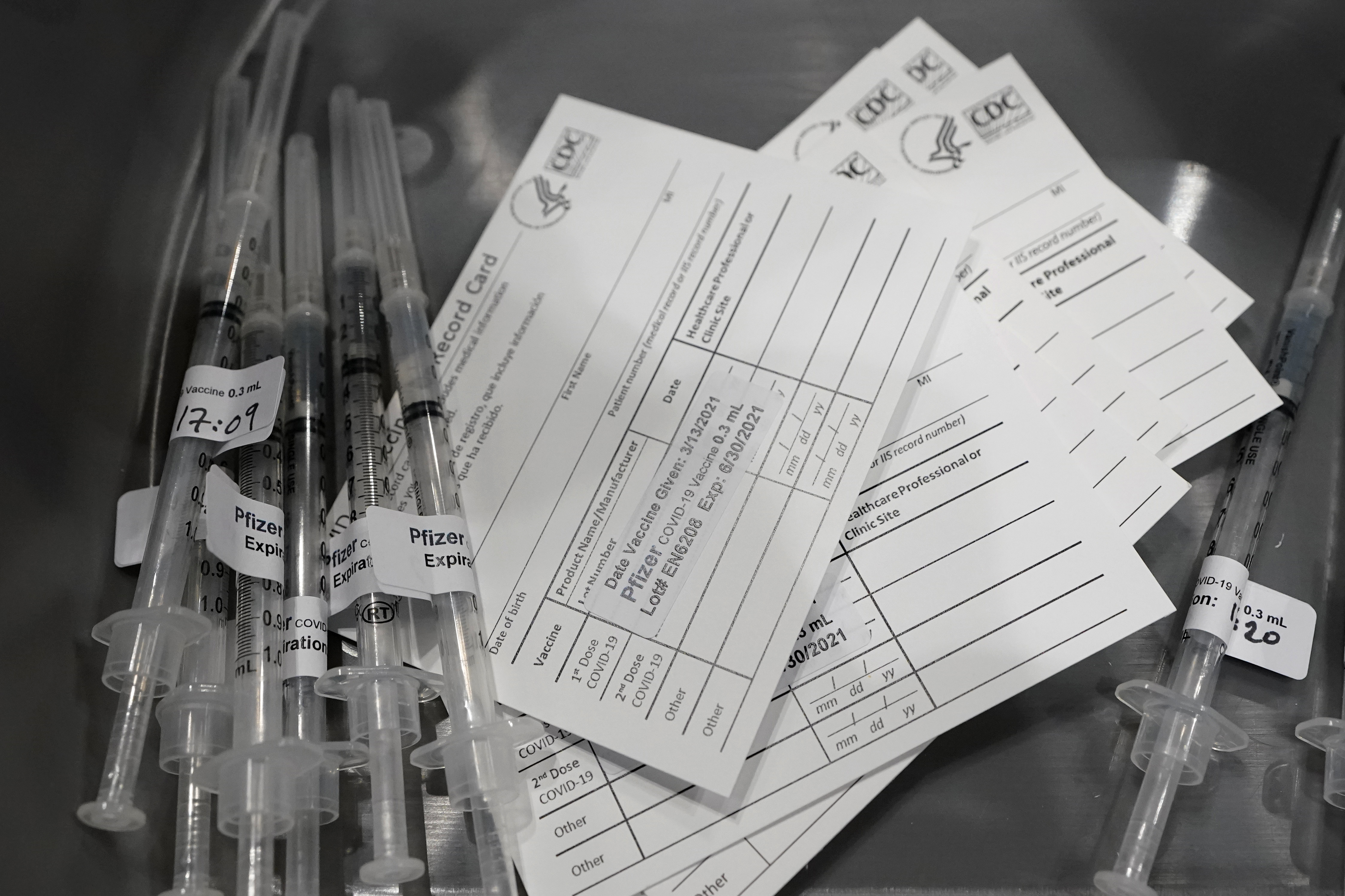

Across private industries, the quits rate was 3.4% while 1% of government workers quit amid inflation concerns and federal vaccine requirements. Overall, the number of quits increased 164,00 versus the previous amount.

In the accommodation and food services industry, 6.6% of employees quit. It was the second month in a row where the number of Americans quitting was a record high. In August, 4.3 million quit.

While the job report in October showed signs of improvement, with 531,000 new jobs added. It’s important to keep in mind that new jobs added means new job openings, not positions filled. The national unemployment rate in October 2021 was 4.8%.

BLS data showed that weekly earnings actually decreased over the preceding year, a 1.6% drop from October 2020’s wage levels across the U.S.

“From April 2020 to March 2021, the 12-month changes in real average earnings were all increases, between 4.0 percent to 7.4 percent,” the BLS reported.

Weekly earnings started decreasing in April 2021, after 14 months of continuous growth.

Ongoing inflation concerns are still causing prices to rise and housing costs have continued to increase, neither show any signs of slowing down. While some businesses are hiring workers at higher wages or offering competitive incentives to grow their employee pool, the national weekly wage level dropping as everything consumers need to buy gets more expensive complicates economic recovery options.

Another factor in worker retention is job flexibility. The BLS reported that 55.6% of workers in 2021 were able to take “short, unscheduled breaks throughout the workday.”

Additionally, less than half of American workers were able to choose between sitting or standing while working, in civilian jobs. Less than 20% could choose their own pace or which tasks to work on, and less than 10% were able to do “critical job functions” while working remotely.

In terms of how COVID has changed the workforce during the pandemic, the shift to remote or telework was a boon to industries with office work, such as finance, computer science, law and legal, or community and social service.

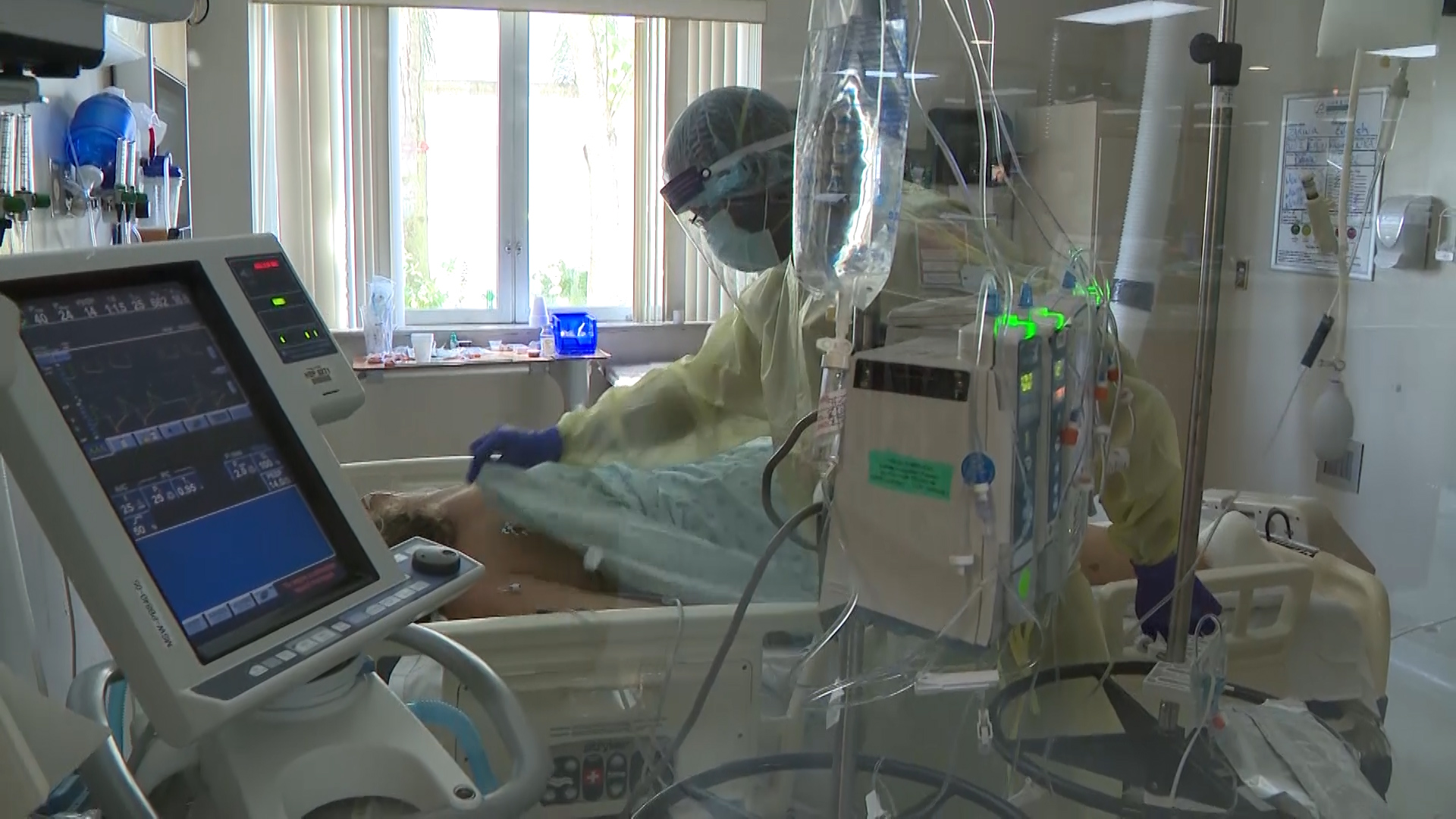

On the other end of the labor spectrum, manual labor workers had to remain at work, in person, whether it was a factory job, farming or in the service industry, if the businesses remained open. Still, telework options weren’t available to everyone in industries that allowed it.

“In 2021, the ability to pause work was available to 97.3 percent of workers in management occupations and 95.3 percent of workers in computer and mathematical occupations,” according to the BLS. “The ability to telework was available to 29.6 percent of those who worked in management occupations and 47.6 percent of workers in computer and mathematical occupations.”

Workers’ ability to set their own pace, sit or stand, and take a short break for something like using the bathroom or getting a drink of water, are cultural factors in the workplace. While the BLS data doesn’t show if flexibility contributed to the record number of quits, COVID-19 has changed how work is viewed and understood.

A Gallup poll on the so-called Great Resignation, the record number of quits, found that many workers left their jobs over a lack of engagement at work. The decision to quit came down to three main reasons, according to the poll.

- Not seeing opportunities for development

- Not feeling connected to the company’s purpose

- Not having strong relationships at work

As inflation continues, affecting everything from the cost of gasoline to groceries, adding new jobs isn’t a cure-all. Inflation is hitting the market in every way, and wages aren’t keeping pace. The Dec. 3 “Employment Situation” report from the BLS could provide insight into what the path to economic recovery looks like in 2022.