TAMPA, Fla. (WFLA) — Dr. Liv Williamson describes this summer as a gut punch.

As a coral restoration scientist at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School, she watched in disbelief as years of painstaking work were destroyed in weeks during this summer’s unprecedented marine heatwave.

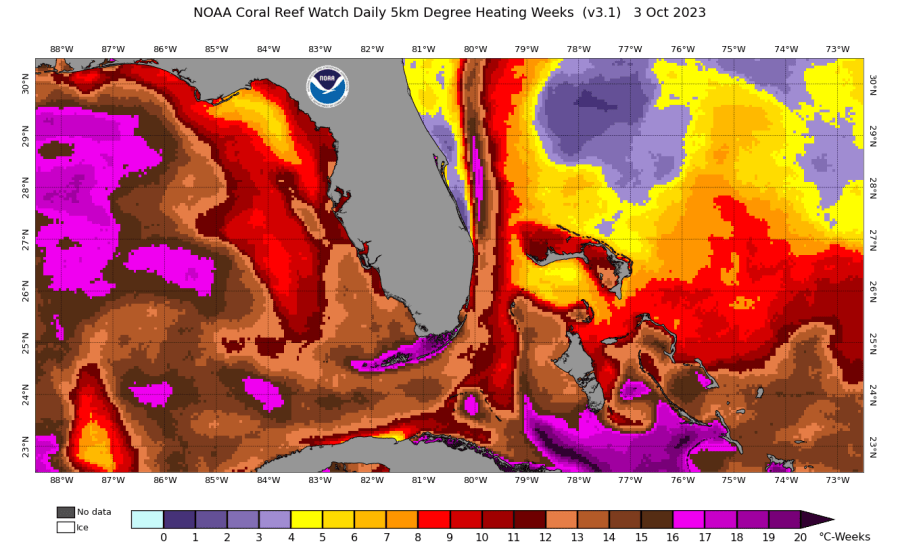

Starting in June, South Florida coral struggled to survive – many failing – in a relentless marine heatwave with unmatched intensity. At times temperatures at the coral reefs neared 93 degrees Fahrenheit near the surface with barely any cooling at the reef bottom.

Twenty-plus weeks of heat stress piled on the vulnerable coral, more than doubling the former record.

The jury is still out as the final death toll, but it was extensive. Williamson says certain coral species were no match for the climate change-driven disaster succumbing in weeks. Most heartbreaking, she says, was watching what coral scientists spent years growing and outplanting, vanish in the blink of an eye.

But Williamson says there is actually good news. Some coral look like they will survive and certain species proved to be more resilient. So as devastating as this summer was, it will act as a massive – albeit unintended – science experiment and learning experience.

As you will see below in Williamson’s Q and A with WFLA Chief Meteorologist and Climate Specialist Jeff Berardelli, some very important lessons were learned. Now, it’s more clear than ever, that “drastic measures” are needed to save tropical coral from ever-increasing human-caused climate heating.

Berardelli: Can you tell me a little about your work and why you do it?

Dr. Williamson: I work on coral reef restoration and developing strategies to make the corals we put back onto the reef more resilient – that is to say, more heat tolerant or disease resistant, so that they can survive in present and future oceans without succumbing to climate change and human impacts.

Berardelli: I know you and many of your colleagues have been working to painstakingly restore coral reefs. This summer must have been a gut punch?

Dr. Williamson: It has absolutely been a gut punch. In theory, we knew that a severe bleaching event like this was going to happen at some point, but knowing that in your head still does not prepare you for seeing it happen before your eyes, and watching many of the corals that you’ve grown to care for die. Especially for the folks who have outplanted so many staghorn and elkhorn corals in the Keys over the years, and watched them thrive and grow and reproduce and become vital parts of the ocean ecosystem, watching them bleach and die in a matter of weeks this summer was completely devastating and demoralizing.

Berardelli: After a summer of record-shattering water temperatures, what is the status of South Florida coral now at the end of summer? Will some survive?

Dr. Williamson: We won’t know the final outcome for another few months, because although the temperatures are beginning to come down from these record highs they are still pretty high. The extent of bleaching and mortality that we’ve seen depends on where along Florida’s Coral Reef you are – the further south, such as the lower Keys, the worse off things seem to be because the extreme heat started there first (as early as late June). It also really depends on species – elkhorn and staghorn corals seem to have been hit the hardest, with corals in Miami and further south in the Keys and the Dry Tortugas showing extensive bleaching and mortality, while hardier species like brain and star corals had a wider range of responses and in many cases will survive and recover.

Yes, most coral will survive! Although bleaching was extensive and severe in many species, it looks like many corals, including important species of brain and star corals, will recover. What is very concerning is that many, and I’d argue most, staghorn and elkhorn corals bleached and died, especially in the Keys. Fortunately, some staghorn in Miami and further north seemed to avoid severe bleaching, and will survive and recover.

Berardelli: To what degree do you think climate change is to blame for the mass bleaching and mortality event?

Dr. Williamson: Climate change is almost entirely to blame. This year is especially bad because it is also an El Niño year, which makes things abnormally warm in the Caribbean, but El Niño is a naturally occurring fluctuation of conditions that occurs every 5-7 years and has done so for a long, long time, and we haven’t seen anything like the scale and severity of this year’s bleaching and mortality in Florida before. The record-breaking extremes from this summer are El Niño conditions exacerbated by increasingly severe global climate change.

Berardelli: Regarding restoration work… did any of the restored coral survive? Did you learn anything about which species are more resistant or better methods to make them more resilient?

Dr. Williamson: Yes, plenty of restored corals have survived! It is mainly the staghorn and elkhorn that died en masse, primarily in southern Miami and the Keys. Those are generally the most heat-sensitive species, and in the regions that experienced the highest accumulation of high temperatures. In contrast, most restored corals in Miami-Dade and Broward seem to have survived and avoided the worst. In addition, species like star and brain corals in many cases proved to be more resilient in the face of extreme heat than the staghorn and elkhorn corals, so many restored corals of these species survived (even in the Keys). Various methods that we have been developing to make corals more resilient, such as manipulating their algal symbiont communities in favor of more heat-tolerant algae or assisted sexual reproduction to breed new generations of corals with new combinations of genes that might help make them more resilient, need to be scaled up going forward.

Berardelli: There’s a lot of admiration for the work you do, but do you feel that coral restoration can keep pace with climate change? Is there a preferred technique that may pay high enough dividends to outpace warming waters?

Dr. Williamson: This event really highlighted that for the more sensitive species like staghorn and elkhorn, traditional coral restoration – the process of growing and planting lots of corals on degraded reefs to replace ones that have been lost – will not be enough in the face of continued climate change. What we really need to do is adopt more drastic measures to manipulate corals, through a combination perhaps of their genetics and microbiomes, to be able to withstand extreme temperatures. Here in Florida, the existing diversity we have just won’t cut it – we need to breed corals with the highest heat tolerance together, and maybe even with corals from outside of Florida that have new and different genetic traits, to create new generations of corals with high diversity and resilience. Even then, with extremes like we saw this summer, time is running out – if we do not address the root cause of these extremes and curb carbon emissions to slow and eventually stop climate change from progressing, we can only hope to buy time for corals. If temperatures continue to warm out of control, the sensitive species like elkhorn and staghorn probably don’t stand a chance, and more and more species will succumb.

Berardelli: Anything else you want to add that you think is important for the audience to know?

Dr. Williamson: The way to help save coral reefs is taking urgent climate action now to curb emissions and reduce the rate of warming. Without that, scientists can only buy time for these important animals and ecosystems, but they cannot do so indefinitely if we create a world that is inhospitable to life.