BRADENTON, Fla. (WFLA) The program set up to handle medical care for survivors of the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, is running out of money and many of the people who depend on the coverage are running out of patience.

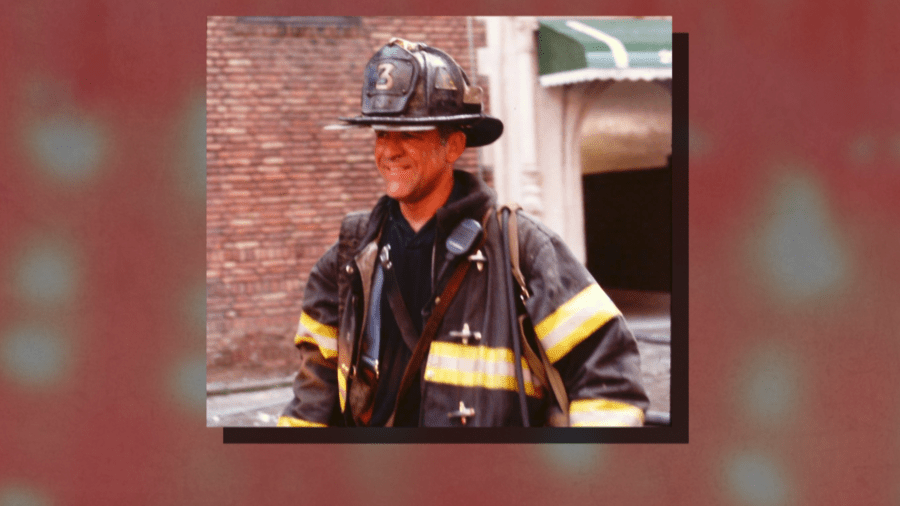

Garrett Lindgren was leaving a Queens firehouse after serving an overtime shift when the attack we saw on television started to unfold in front of him.

“I’m heading over the Triborough Bridge. I hear on the radio there’s a fire at the World Trade Center,” Lindgren recalled. “I saw a massive hole in the side of the North Tower.

The images are still fresh for Lindgren, one of about 450,000 survivors who qualify for coverage under the 2010 World Trade Center Health Program (WTCHP) WTCHP hired Wisconsin-based Logistics Health to run the program.

“I have health issues that just continually remind be of 9/11 between the asthma and the chronic sinusitis and reflux,” Lindgren said. “Little did I know I was going to need two inhalers for the rest of my life.”

Minutes after seeing the North Tower on fire, every New York City firefighter was called in to help.

“My last words to [my wife] was you know I love you,” Lindgren recalled, “And tell the kids I love them. A lot of us were going to die there.”

Lindgren was so determined to get to ground zero to help, he did not focus on a grim reality. Everyone near the attack that morning would inhale toxic dust and smoke for hours.

“It was like being inside a burning building where we normally have zero visibility. Only, we’re in the street,” Lindgren said. “We were bumping into overturned ambulances and police cars. There were fire trucks that were on fire and dead silence.”

In that toxic and quiet darkness, on what had been a sunny morning in New York City, Lindgren and his crew searched for survivors.

“My whole first day there, I actually had my hands on two stretchers of people that I know for a fact survived,” Lindgren said. “And for one woman I got to just to put my hand on that stretcher and offer her some words of encouragement.”

Nearly 3,000 were killed including 343 firefighters and early on Lindgren was listed as one of the missing.

“So, now I called my wife,” Lindgren said. “When she realized it was me, she said she just fell to her knees in our kitchen. It just overwhelmed her.”

Two decades later, Lindgren is among the survivors who are frustrated by what is not covered by the WTCHP, including toxic neuropathy.

“My arms and my hands and my legs and my feet are heavy all the time. Sometimes they almost feel like they’re made out of concrete,” Lindgren said. “And I’ll just get bolt of pain, like I got hit by lightning out of the blue.”

But not covered at this time by the WTCHP

“The dioxin level that we were exposed to was 100 times higher than any reported exposure ever,” Lindgren said.

He also hears from friends about the program’s inefficiency.

“It’s a million phone calls. He gets a prescription that’s hundreds and hundreds of dollars,” Lindgren said. “And they go to the pharmacy to pick it up and they still didn’t approve it.”

Lindgren said he wouldn’t change risking his life that day, but he is adamant that the survivors deserve better.

“This is bigger than bigger than all of us,” Lindgren said. “It’s something that individuals can’t take care of on their own and it’s troubling that this is going on.”

One projection indicates the WTCHP will be in the red within about five years with a budget shortfall of nearly $3 billion. A bill was introduced last month by Reps. Jerry Nadler, D-NY and Andrew Garbarino, R-NY to provide more funding.

The WTCHP covers dozens of issues, including several forms of cancer. The most common ailments include COPD, GERD, asthma and anxiety disorders.

The program does allow patients to petition for additional coverage and there is also an appeal process for denied requests.

There are also complaints about outreach by the WTCHP that some blame for on the relatively low number of survivors who are enrolled.

Lindgren hopes the program will improve in the coming years.

“I know there’s a lot of good people involved in these programs that want to help us,” Lindgren said. “But they’re not the ones that that get to flip the switch or make it happen.”